If I forget you, Jerusalem

Recalling abuse or injustice can be excruciating. But it’s vital for us to process our grief and anger. Doing so here, the psalmist resolves to cling to her hope of Jerusalem’s restoration, no matter what.*

1 By the rivers of Babylon

we sat down and wept

as we remembered Zion.

2 There on the willow trees

we hung up our lyres

3 because our captors asked for songs

and our tormentors wanted a laugh:

“Sing us one of your good ol’ Zion songs!”

4 But how could we sing any of YHWH’s songs

there in a foreign land?

5 If I forget you, Jerusalem

may my right hand forget all it’s ever learned.

6 May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth

if I don’t remember you

if I don’t count Jerusalem my highest joy!

7 Don’t forget what the Edomites did, YHWH

on the day Jerusalem fell—

how they said, “Raze it!

Raze it down to its foundations!”

8 Beautiful brain-bashing Babylon

doomed to destruction:

Blessed is the one who pays you back in kind

for what you did to us.

9 Blessed is the one who grabs your little ones

and bashes them against the rock.

Beside the same rivers that nourished Eden’s beautiful trees, the psalmist’s tormentors demanded songs celebrating Zion’s unrivalled place in the world. Having destroyed Jerusalem, they now wanted to turn its destruction into fodder for their mockery. The psalmist and her fellow captives refuse by hanging their lyres on the willows, the trees now representing not abundance, but rather devastation, loss, and anguish.

Zion was where God lived to manifest his just rule on earth, offering grace and peace to all who sought shelter in him. Far from just being an ethnic dream, Zion signified God’s redemption of humankind and the entire world. The psalmist refuses to give that dream up, though she can’t reconcile it with her exile to Babylon either. With everything else stripped away, she refuses to abandon her vision of Zion, no matter how impossible it now seems. In fact, she’d rather endure a stroke—with its familiar symptoms of impaired movement and speech—than give up on that hope because life isn’t worth living without it.

Now her images of Zion ring with harsh Edomite cries and blind her with visions of Babylonians smashing Israelite babies’ heads against the rock. Those sounds and sights signify evildoers’ attempts to end the hope Zion represents. This seems an all-too-human outburst of vitriol on the psalmist’s part. But it is in fact her declaration of faith in God’s promise that justice will be done because Isaiah had prophesied that God would ensure that the Babylonians’ evils were done to them in turn (Isa. 13:16). The psalmist shockingly blesses those who will execute that sentence. She thus gives her pain and anger to God, accepts his judgment, and turns vengeance over to him.

Prayer:

Lord, I hate seeing brokenness or pain. But you’d also have me resist evil and weep with those who weep, not pretend all is well here in Babylon. Help me accept that compassion demands justice, which must always be on your terms, and that seeking your kingdom first involves this too. Amen.

In your free moments today, pray these words:

If I forget you, Jerusalem

may my right hand forget everything it’s learned.

May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth

if I don’t remember you

if I don’t count Jerusalem my highest joy!

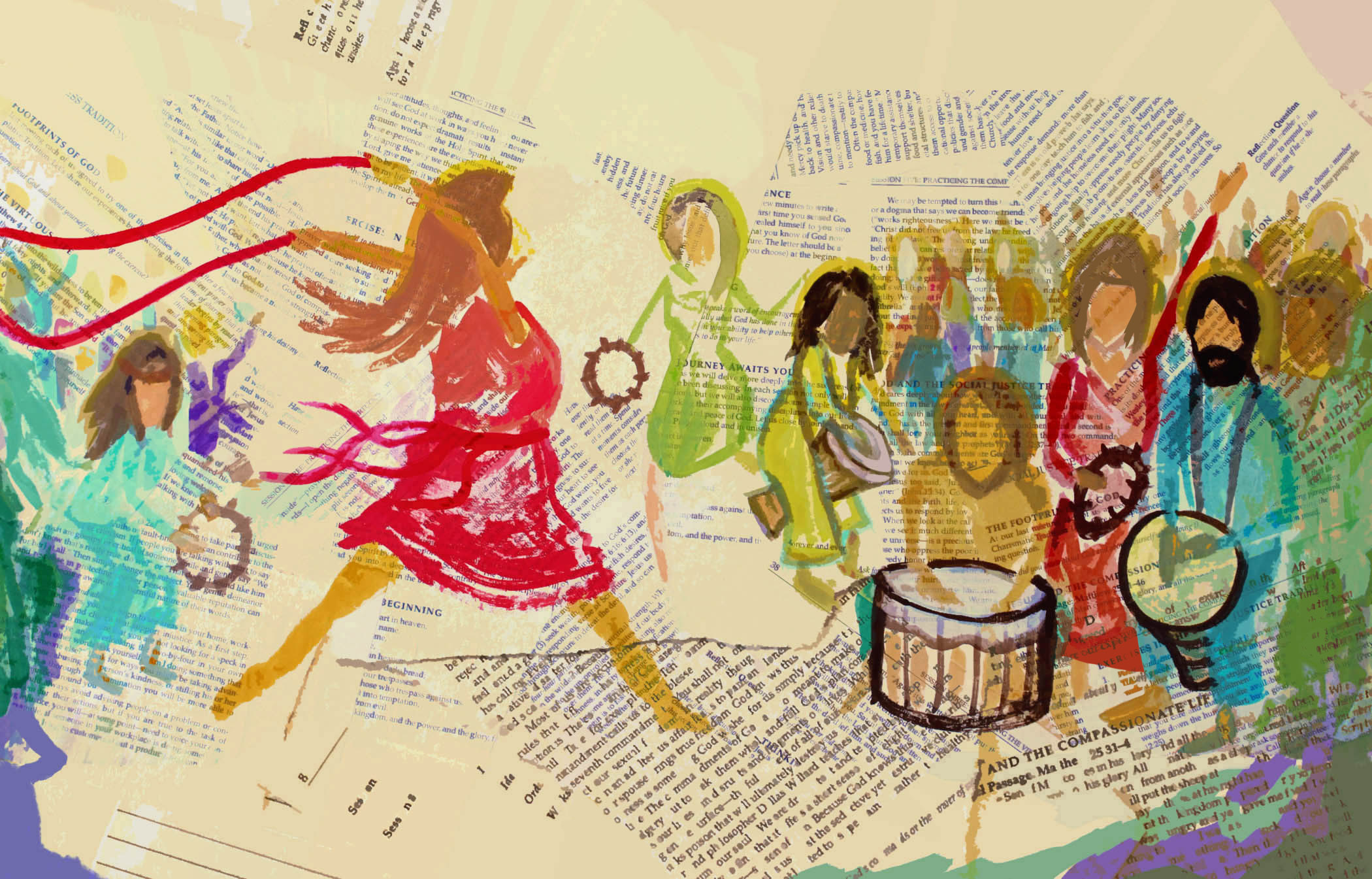

* I imagine the psalmist here as a woman of faith, like Miriam, Deborah, Hanna, or the Virgin Mary (see further, my answer to the question: Who wrote the psalms?).